I'm on a roll,

I'm on a roll to success

I feel my luck could change

- Radiohead, "Lucky"

I'm playing one of my first games of Hearthstone since discovering a recipe for the so-called "Doctor Draw" deck that I'm now using. I've been playing Hearthstone for a few weeks since rediscovering it after they added iPhone support, but this is the first time that I've sought out advice for deck building online. This is a Priest deck; the Priest class revolves around healing and board control, and this particular deck features a card called the Northshire Cleric, which allows its owner to draw an extra card every time a minion is healed. Late in the game, after withstanding an early rush from my opponent, I play Holy Nova, which damages all of their minions and heals all of mine. This clears their side of the board and gives me four extra cards, one for each minion of mine that was damaged at the time. As my hand filled and it became clear that I had the match well in hand, I suddenly felt a rush I hadn't felt in a long, long time. And it felt really good.

My high school gaming experience was all about two types of games: Fighting games and card games. I didn't get an NES until I was 11, and then not until 1990, very late in that system's life cycle. The Super NES came out almost immediately afterward, and that was a non-starter, as far as my parents' willingness to buy one was concerned. I had wanted the NES, I had begged and pleaded for nothing but the NES for five years, and so the NES (and the Game Gear that I got for my Bar Mitzvah, because I was swayed by pretty colors to make the terrible decision to not get a Game Boy) would have to do. The NES would be the last console I'd get until my wife-to-be and I would pool our money in college one summer and get the N64 that would be our first joint possession of many. I had a PC, but most of what I had were Sierra games and Doom, neither of which I was ever able to get the handle of to the point where I could really enjoy them.

This means I missed out on a lot of important games that I had to catch up with later. For some things, this was no big deal; I've since played through Super Mario World and A Link to the Past, and I recently finished Super Metroid for the first time thanks to the virtual console on the Wii U. However, the one game that I was never able to catch up on was Street Fighter II. That's not to say I've never played the game; of course I have, but there's a difference between playing Street Fighter II once in a while at a friend's house or in the arcade and having ready access to it. I could play Street Fighter but I could never really get good at it; that takes the kind of time and obsessiveness that you really only can get as a kid or a teen, the same kind of drive and ability to learn that let me get good enough at NES games to get to the very last stage of Battletoads, past the speeders and the giant snake levels.

There are different levels of play in a fighting game. Anyone can just pick up and play, hit random buttons, and hope to get lucky once in a while. That was the level I was always stuck at, where I was a world class button masher but could never really get to the next tier of play. What happens once you actually learn a fighting game, when you get to the point where you're not just pressing buttons randomly, but you know what each button does for the character you chose and when each button is to be pressed, is that magic starts to happen. All of a sudden you can go from randomly hitting and getting hit to being able to counterattack reliably, and even execute combos that your opponent can't answer. In other words, at some point, the game seems to slow down for you. This is the level I always wanted to get to in Street Fighter, and it remained a constant frustration that I couldn't, no matter how hard I tried. It could be that my reflexes were never fast enough, or I never played with the right people who could teach me what I was missing, or I just missed my window of opportunity to learn how to play those games correctly. Maybe it was all three. Whatever it was, the game never slowed down for me. No fighting game has.

I had very few friends in high school, which is something that should come as no surprise in any retrospective that revolves around video games in the 90s. Up through 8th grade, I was in a Jewish day school that dwindled to a graduating class of twelve; everyone more or less at least tolerated each other because there wasn't much choice otherwise. I moved to the public high school in 9th grade, which was considerably larger. Once I went from being a big fish in a small pond to a small fish in a giant pond, I needed to learn how to swim very quickly, and I never really did. I was either lucky or smart enough to stay out of the line of fire of the bullies, for the most part; I never got physically beaten up, though the threat was always there, that one wrong move would lead to Beatdown City. I mostly kept to myself, kept my head down, and stayed out of trouble. I was terribly lonely a lot of the time, though.

My sophomore year, I became friends with Ryan, who would end up being one of the only real friends I'd have in the school during my time there. Being outside the generally accepted "cool" social circles, we did the only other thing there was to do as a teenager in New Jersey in the mid-90s: We went to the mall and walked around without buying anything. (When I was eventually exposed to the movie Mallrats, it felt like it was a story tangentially about my life; I actually recognized more than one of the malls they visited in that film.) Once the mall closed or we just got bored of doing what we called "the ritual" (read: a loop around the mall with obligatory stops at stores like Electronics Boutique and Spencer Gifts), we would go back to his house and play video games. Ryan had a Sega Saturn, and the only games worth playing on it that he owned were Japanese imports of X-Men vs. Street Fighter and Marvel Super Heroes vs Street Fighter. We'd play for hours, and I'd be lucky to win a match in any given evening.

I desperately wanted to get better at the game, to feel like I was good at something. I was perpetually on the honor roll, so I was good at academics, but that didn't really count for me at the time. That wasn't valued, I thought, by anyone except for college admissions officers who would eventually look at my GPA, and they were in the future. Being good academically certainly wasn't winning me any friends, because it became abundantly clear early on that, as far as the social order of high school was concerned, my intelligence was a negative trait, and I would be punished if I were to try to make it otherwise. Video games were something I felt like I could be good at, and fighting games were the only kind of game that was out at the time where I felt like I could prove that competitively. I printed out move lists from GameFAQs and studied them, to no avail. Try as I might, it just never happened.

Around the same time, I went into what would become my regular comic book store and noticed the display of Magic: The Gathering cards on the counter. This was an easier sell to my parents than an SNES or a Playstation; instead of needing a $200-$300 console, all I needed was a $12 starter deck. The math was easy, at least at first. I fell in love immediately. Before I knew it, I was a regular at the comic shop's Magic night every Sunday. That became a fixture of my high school life from that point on, and I rarely missed a week; it was the one thing I had to look forward to at the time. No matter how bad the week got, no matter how mean the kids were to me at school, I knew that as long as I could make it to Sunday night everything would be ok, at least for a little while.

What's more, I was actually good at Magic in a way that I never really could be with fighting games. Magic is a really difficult game; the basic rule book is fairly thick, and the game actually gets more complex as different cards interact in ways that the rule book doesn't always cover. That never really bothered me, though; it made sense to me as though I'd been playing the game all my life. The intricacies of the game, like how to balance a deck, how to make the most of the cards available in any given situation, and how to bait an opponent into using up defensive cards on decoys before playing important cards, came to me relatively effortlessly. The same skills that would eventually make me a good programmer also made me a good Magic player; every situation was a problem that I needed to use a set of tools to solve, and I was good at putting the pieces together on the fly. As helpless as I felt playing fighting games, that's how confident I felt when playing Magic. They both put me one on one against another person, but when playing Magic, I knew what to do and I knew how to do it. I could finally win at something.

Magic: The Gathering quickly became more than a game to me. It was an opportunity, once a week, to sit down across the table from someone and prove that I was actually good at something that mattered to my addled teenage brain. Playing Magic went from being something I did to being something I was. I had binders full of uncommon and rare cards meticulously catalogued, despite the fact that everything else I owned was perpetually in a series of piles on my bedroom floor, a dichotomy my parents pointed out frequently. (In retrospect, I either was hyperfocused on keeping the cards organized or Magic was so important to me that I was able to push past the attention issues that I didn't yet know I had to get them in order.) I found channels of Magic players on IRC and downloaded a program that simulated a card table online to be able to play practice games during the week. I spent whole evenings reading web sites on strategy and deck building. School was easy for me at the time; the real study time went to Magic, not academics.

To be clear, I wasn't ever professional level good; that kind of proficiency took a monetary commitment I was never able to make. I don't know that I even won more matches than I lost, looking back on it. I certainly didn't win enough to cover the cost of the cards I needed to buy. But I held my own in the weekly tournaments at the comic shop and the bigger tournaments that were held in the area. I even got to the quarterfinal round in a large sealed deck tournament in Boston toward the end of my freshman year of college; the challenge of beating that many opponents in a row was equalled by the challenge of trying to find a taxi out of downtown Boston at 2:30 AM after I was finally eliminated.

Eventually, though, the cost of the game caught up with me. New expansion sets came out three times a year, on average, and getting the new cards was necessary to stay competitive. My reward for getting on honor roll for a quarter was a box of booster packs, which usually ran between $100 and $150; it was like an extra birthday every time I got one of those, because I spent the whole day opening presents. Once I was in college and on a limited budget, though, the idea of spending that much money to just be able to keep playing became too much. I moved over to sealed deck for a while, but that was never as fulfilling as being able to put together a deck I knew like the back of my hand. After my freshman year of college, I gave Magic up cold turkey one day and didn't look back.

Ultimately, by then I didn't need Magic anymore. When I got to college I found a supportive environment full of people who accepted me as I was, so I didn't feel the need to prove my worth constantly, either to myself or others. A few months after I gave up Magic I met the woman who would eventually become my wife. Magic wasn't a lifeline to get me through the week anymore. It became just another game, and an expensive one at that, so when I closed up the boxes full of decks for good I didn't feel like I needed to open them back up again.

One of the things I learned since being diagnosed with ADHD is that, the later in life you're diagnosed, the more damage is done to your self esteem and confidence. What's happened to me as a result of being plagued with inconsistent attention is that I stopped believing that I could actually do the things I'm good at. In general, the expectation is that once you acquire a skill, it's something that's repeatable. Once you're sufficiently skilled at riding a bike, for instance, you're not going to suddenly not be able to ride it again, for instance. For people with ADHD like me, though, failing at something you should be able to do easily does happen. I've had spells of time where I'd stare at a daunting piece of code for weeks and not be able to figure out what needed to happen next, and then one day I'd sit down, somehow trigger a bout of hyperfocus, and crank through the whole thing in an hour or two. Or I'd be able to master a really complex technique but not be able to grasp basic concepts in a related area that really aren't that complicated, but I couldn't get my brain to focus in on.

Unfortunately for me, I managed well enough as a kid to evade an ADHD diagnosis. I got good grades despite rarely taking a book home to do do homework. I wasn't hyperactive or disruptive; if anything, I was the complete opposite, staying quiet and out of the way. To the people around me, when things that I was clearly capable of didn't get done, this meant I was either lazy or didn't care. I could seemingly do things when I wanted to, so when I didn't, the explanation had to be that I was blowing them off because they weren't important enough to me. The thing is, I did care about what it looked like I was blowing off a lot of the time, but I couldn't get myself to stay focused on those things long enough to get them done. It wasn't that I cared only about the things I became hyperfocused on, like Magic, but rather the things that would trigger hyperfocus were the things I started to care about more than anything else; those were the areas where I knew I could maintain my focus long enough to do what I needed to do.

The problem with hyperfocus is it's difficult to predict when it will kick in. Very often, without the benefit of hyperfocus, tasks felt daunting or impossible. What's worse is that hyperfocus would sometimes leave me high and dry in situations where it had been my saving grace before. This happened enough that I started to question whether the skills I had were really skills at all, because a skill is something that you're supposed to be able to rely on; my skills never felt reliable to me. It was almost random if I'd be able to make use of one of my skills on any given day, as though I was waiting for the right card to come to the top of my internal deck before I could use it. So if what was getting me through life wasn't skill, then the explanation is obviously that I got lucky. So if I've been getting through life on luck and not skill, what happens when that luck runs out, as luck always eventually does?

Taking this all the way to its logical conclusion has left me with a pretty severe case of impostor syndrome, for pretty much every aspect of life. I could look at everything I'd accomplished, be it honor roll in high school, or graduating college, or a performance appraisal or anything that was a proof of my accomplishments, and I wouldn't feel like I earned them, or at the very least that I didn't deserve them. I knew all the places I messed up along the way. I knew all the times that I couldn't do what I needed to do, or I could do it but couldn't will myself to do it, and felt like luck got me through. Even now, knowing what I know, and that what I've accomplished is real and maybe even more impressive because I overcame undiagnosed ADHD to accomplish it, it's very easy to go back to that dark place.

I think a lot about failure these days, since it tends to affect me so strongly. Little failures can lead me to beat myself up for a while, especially when I should know better. A bad day where I see the results of several small failures at once, or one big one, can leave me in a funk for days that's very difficult to pull myself out of. I'll tell myself that I'm in over my head, or that I'm a fraud, and that people are going to find out and then everything I've gotten (not earned, never earned) over the years is going to come crashing down like a house of cards. This has gotten better since the diagnosis; I can recognize the failure for what it is and not see it as a harbinger of doom. Even now, though, it takes a lot of effort to see past the yelling voices and realize that the good outweighs the bad. As a result, I'm less likely to put myself into situations where I know I'm likely to fail a lot; I know how that can snowball and it's not good for me.

What I realize, knowing what I know now, is that what made Magic different was that failure wasn't a sign of weakness or that I wasn't good enough; it was an expected part of the game. Sure, luck got me through when I won, because luck was built in. No one wins without getting at least a bit lucky, and any loss could be dismissed by a bad starting hand or the wrong card at the top of the deck. It was the one place where I could compete on equal footing and be legitimately proud of whatever I accomplished, and when things didn't go my way, I could dust myself off and come back the next time because I knew that was just part of the game. I'm only now realizing how much I needed Magic at a time in my life where I didn't feel like I could be good at anything that was important to me.

I try to get back there sometimes, when the failures start to pile up and I need to feel like I'm good at something among everything feeling like it's falling apart. Card games have been out of the question since I gave Magic up, both because of the expense and the difficulty of getting somewhere physical to play, so I've tried what I've always seen as the next best thing, which are fighting games. I've made an attempt at playing almost every major fighting game when they've come out. I got good enough at Marvel vs Capcom 2 to be able to beat the computer on medium more often than not, but playing against another human still ended poorly for me, and I was never able to execute any more than one basic (and fairly cheap) combo with Jin. I gave Street Fighter IV and Marvel vs Capcom 3 legitimate chances when both those games came out also. Street Fighter IV in particular had a setting that allowed people to challenge you as you played single player mode. I left that on for maybe a day before it left me too demoralized to continue. I decided, based on that experience, that I was too old to be able to get good at fighting games now.

When Mortal Kombat X came out a few weeks ago, I tried one last time to see if I could ever get a fighting game to click for me. I'd been assured that the fighting system was simpler than other games, and had been tuned to be more accessible for newcomers. I got advice from one of the best fighting game players I know. ("Don't look at your fighter because you know what you're doing; look at the other player so you can react to them.") That said, I gave the story mode several hours, and while I was able to make progress, I never felt like I had any actual control over what was happening on the screen. I was right back to Ryan's room in high school, hitting buttons with no real feeling like I knew why any button should be pressed. I felt no agency over my character; I was entering commands and things happened on the screen, but those two things felt disconnected, as though the result would be the same if I wasn't manipulating the controller. The experiment ended the same as every other one had, with a sense of frustration that I'd failed at fighting games yet again.

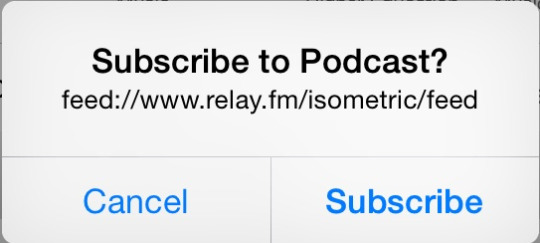

Around the same time, Hearthstone was released for the iPhone. I'd tried Hearthstone when it was in beta; it was a fun game but it had always felt like a really stripped down, basic version of Magic to me. The rule set was drastically simplified compared to Magic, and it felt like all I was doing was lining up minions to fight other minions; there didn't seem to be any deep strategy there to appeal to me. Add to that a client that was slow to load on my Mac, and I quickly forgot about it until I decided to give the game another try on my phone. Once I could load up a game instantly, wherever I was, and I gave it a legit chance, the depth of Hearthstone became apparent to me. What's more, being free to play, I could get into it casually without going down the booster pack treadmill again. I'd lose some games to people who had spent enough money to have a full set of Legendary cards, of course, but that's just going to happen. And I already knew all too well that just having good cards won't win you matches if you don't know how and when to use them.

So I started playing again, taking advantage of the daily quests to maximize my gold to get better cards, and slowly I got better. The first month that I played Ranked mode, it took me a few days to get from rank 25 to rank 20, where you earn a special card back for that month's campaign. The next month, it took me a day. I learned how each of the classes plays, and figured out which ones suit my play style (priest, warlock, druid) and which don't (warrior, mage, hunter). I learned how to build a deck and how to make the cards work together. I learned how to be patient and not to panic from an early game beatdown. I got to the point where I could go into any match expecting to win, and I could brush off a loss and go right back in without feeling like I wasn't really as good as I thought I was.

I didn't realize that I still needed that reassurance, but some days, despite having the diagnosis and knowing my skill is real, I still do. For ten minutes, even if everything else feels like it's going to pieces, I can remind myself that I am as good as I think I'm supposed to be, both in and out of the game. That it's ok to stumble, as long as I go right back in and try to do better the next time. That even a string of failures doesn't mean that the next win can't be a match away. That I don't have to win every time, as long as I can win sometimes, and I know that I'm good enough to win when things go my way. That just because my cards didn't come the right way once doesn't mean my cards aren't good enough to ever win again.

All I have to do is shuffle the deck, draw another starting hand, and remember that I'm as good as I'm willing to let myself be. That's what I needed all along.